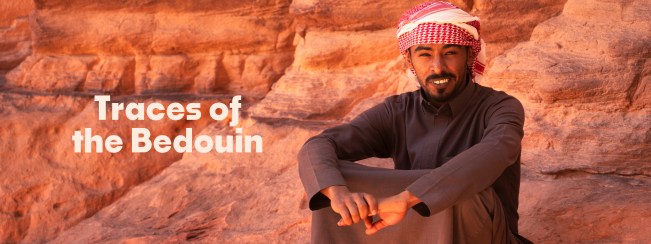

Traces of the Bedouin

Life in the Wadi Rum desert is shaped by the rhythms of the land — the rising and setting sun, the shifting sands, and the rare but welcome rains. For generations, Bedouin tribes have adapted to this harsh environment, building a culture rooted in resilience, hospitality, and deep knowledge of the desert. Traditionally living in goat-hair tents and moving with their herds, the Bedouins developed skills essential for survival, such as finding water in hidden springs and navigating the open wilderness by the stars. Every mountain, canyon, and rock formation in Wadi Rum carries a story passed down through songs and oral traditions.

Today, many Bedouins continue to live in Wadi Rum, blending tradition with the realities of the modern world. Some have opened their desert camps to visitors, offering a glimpse into their way of life through shared meals, camel rides, and evenings by the fire under a canopy of stars. Despite changes brought by tourism and technology, the spirit of the Bedouin remains strongly tied to the desert. Their connection to the land, their sense of community, and their respect for the natural world continue to leave traces across Wadi Rum, visible not just in the landscape, but in the enduring customs that have been carried forward through time.